The Contemporary Revaluation of Tapestry

Unjustly seen as an art of the past, most likely due to the age of its practice, in the contemporary period there is a revival of tapestry, as a result of the democratization of art and the popularization of various new artistic media. In this context, a revaluation of tapestry art takes place through its positive appreciation as a medium of introspection, symbolism, and identity reconstruction. In the current exhibition at WIN Gallery, there are tapestries created by Cela Neamțu, Marijana Bițulescu, and Carmen Tepșan. The three artists offer us very different examples of tapestry from a stylistic point of view, their main focal points being anchored either in the medieval aspect, in symbolism organized around a constantly repeated axis mundi, or in the formal and symbolic fragmentation of the tapestry.

Cela Neamțu encodes within the weave of the tapestry (which also includes embroidery) Umbrae Parvae XIV a non-religious, airy, implicit sacredness, which is immediately perceived by the viewer. Starting from the numerological elements, the windows in the 4-3-4 arrangement, of which the three central windows are decorated with a twisted column, and ending with the church-like aspect of these windows, the feeling that overtakes you in front of this two-meter by one-meter work is that you are standing before a medieval monument, a possible wall materialized before us. This wall opens to us not only through these windows but also through the light suggested by the color of the fabric, which appears to be organized in three registers: blue/white in the upper part, transitioning to yellow in the middle part, and ending with a dark blood-red in the lower part.

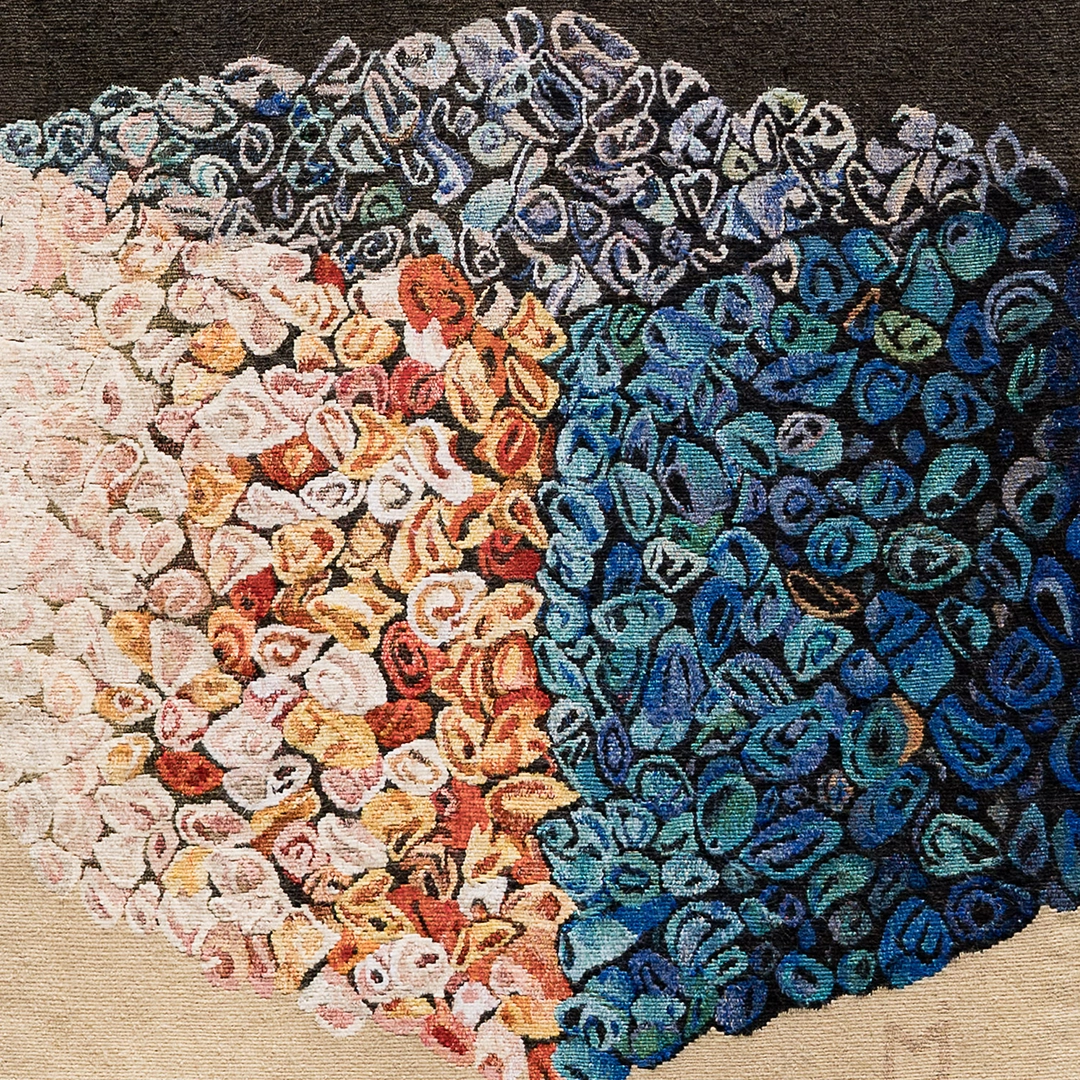

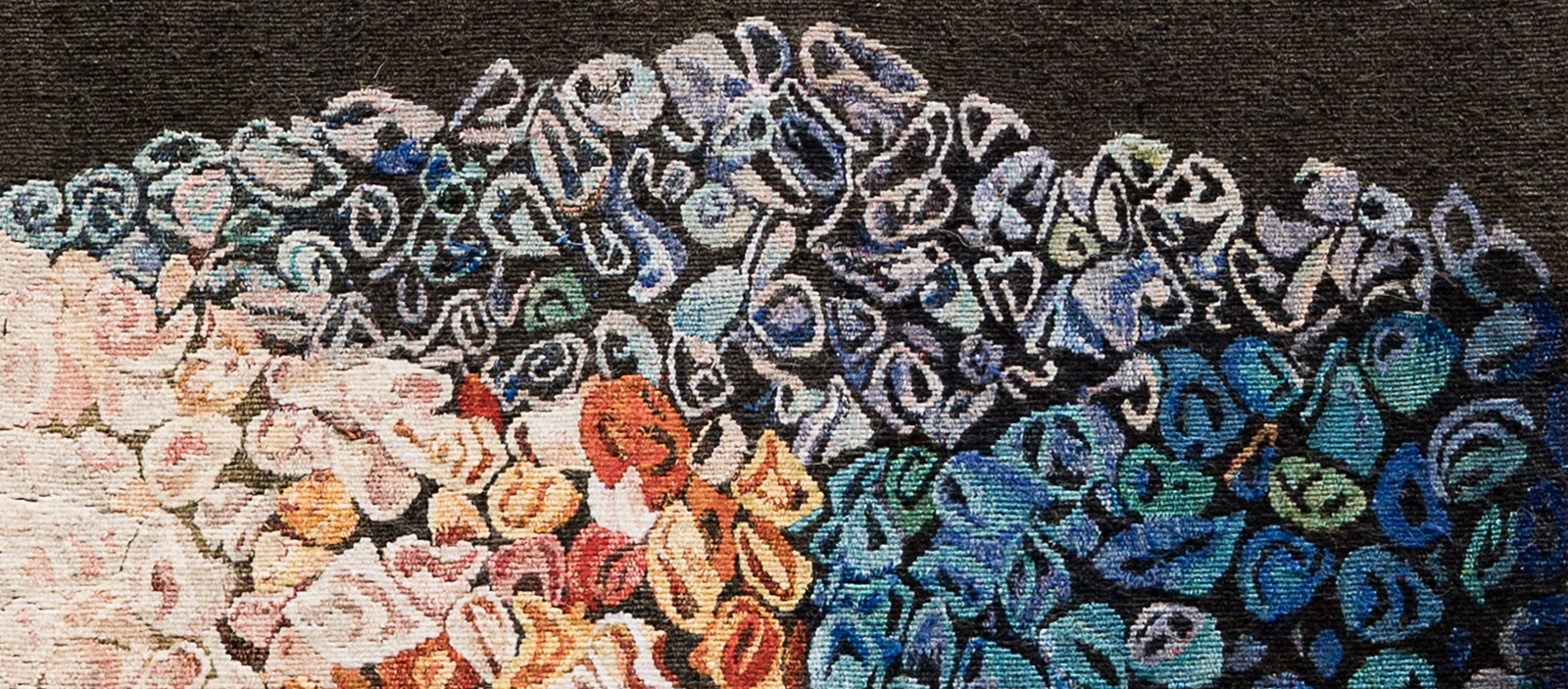

On the other hand, Marijana Bițulescu seems to organize the works in the current WIN Gallery collection around an axis mundi repeated in various forms. Beyond the tapestry titled Axis Mundi, the work Construction – The Price of Progress brings to the viewer’s attention the fact that this "price of progress" may be natural beauty itself. In Marijana’s tapestry, a golden column encircled by red fabrics, similar to construction reinforcements, is split vertically, with an amalgam of flowers and leaves visible inside. The contrast between artificial and natural is thus revisited, the tapestry offering us a meditative exercise on the topic of limitless development and the cost that, sooner or later, we must pay.

Lastly, Carmen Tepșan offers another example of tapestry through the work Triptych. It stands out through a vertical triptych composition, in which space is fragmented into distinct color bands: blue, yellow, and gray. These suggest a discontinuous narrative rhythm, like a visual reading in sequences. The figure of the giraffe, a recognizable element placed in the center, introduces an organic and archetypal register, in contrast with the abstract arrow form and the deformed anatomical shapes on the right. The tapestry seems to place in tension the animalistic, the symbolic, and the technical, using symbols that invite personal interpretation. The limited but intense color palette offers a balance between the poetics of form and an almost brutalist geometry. This is a work that speaks of internal visual codes, of layered memory, and of how textile matter can become a space of both abstract and figurative thought.