The Object as Memory

In contemporary art, objects without an apparent aesthetic dimension come to acquire a deeply symbolic function when used not only as raw material but as carriers of memory. They become extensions of biography, affective relics that can tell stories without words, building a bridge between the artist’s intimacy and the viewer. Memory is not represented only through image or word, but through the traces left on the surface of objects, from a worn fabric, an old toy, or fragments of furniture. In this context, artists transform everyday objects into elements of visual language, marking them with various personal experiences that viewers themselves come to link with new lines of significance. The gallery or exhibition space thus becomes not just a space of display, but a territory of confession.

A defining example is Geta Brătescu, who transforms her studio into a living space, almost ritualistic, where the artistic act becomes a form of daily existence, and collage a method of self-narration. Geta Brătescu’s very life constituted a true gallery, the textiles, paper, threads, scraps of packaging, or fragments of old clothes not chosen by chance but extracted from immediate domestic life, charged with discreet intimacy. Her artistic practice does not pursue a grand aesthetic, but rather a personal, intuitive logic through which disparate fragments compose a mobile, fragile, and playful feminine identity.

For Louise Bourgeois, the object becomes a witness to a painful personal history. In the Cells series, the artist introduces old beds, broken mirrors, worn clothes, elements that compose a fragile decor yet loaded with emotional tension. The ordinary object thus becomes a catalyst of memory regardless of its personal or collective nature, memory that speaks of fragility, intimacy, and suffering. A bed is no longer just a place of rest but evokes illness, abandonment, vulnerability. A piece of clothing becomes symbolic skin, bearing traces of suffering and loss. A broken mirror does not just reflect the viewer’s image but fragments it, forcing them to see ruptures and dislocations. The works Cell (Glass Spheres and Hands), Cell (Eyes and Mirrors), or Cell (Clothes) are concrete examples in which objects do not communicate through their aesthetic value, but through the emotional tension they trigger. Often, the spaces are constructed so that the viewer cannot fully enter, being blocked by an iron mesh, or by the fact that the objects are placed at an inaccessible angle, emphasizing the idea of withheld intimacy, of trauma that is not fully revealed but merely insinuated.

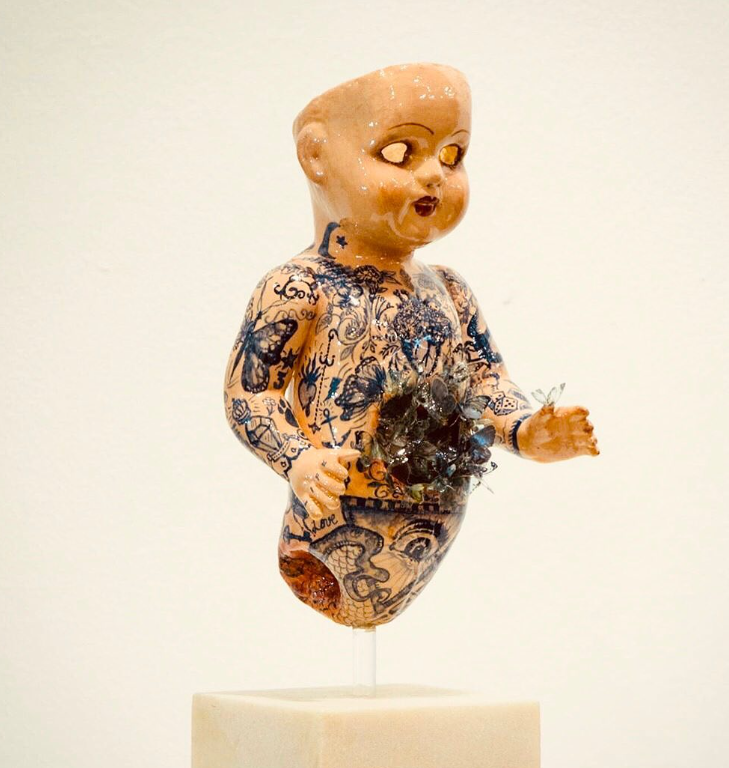

A final example that I care about very much comes from the Lusitanian space, from Portugal, where artist Ricardo Passos brought the theme of memory to public attention through the exhibition Forget Me Not, in 2021. The exhibition explicitly addressed the theme of memory, with works using the image of the doll to express the idea of abandonment. Among the displayed works, the one I constantly return to is a hollow porcelain doll, legless, tattooed, from whose abdomen emerge butterflies made of glass shards. A complex and complete visual metaphor, a direct reference even to Alzheimer’s-type illnesses, Ricardo Passos’s work shows how the fragility of the object can become an expression of a deep human fragility, that of a disintegrating identity, of memory breaking into fragments. In this sense, the object, once a toy and now a relic, becomes a memory-body, an extension of a personal or collective history that can no longer be told in words, but only in a silent and heartbreaking image.

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)