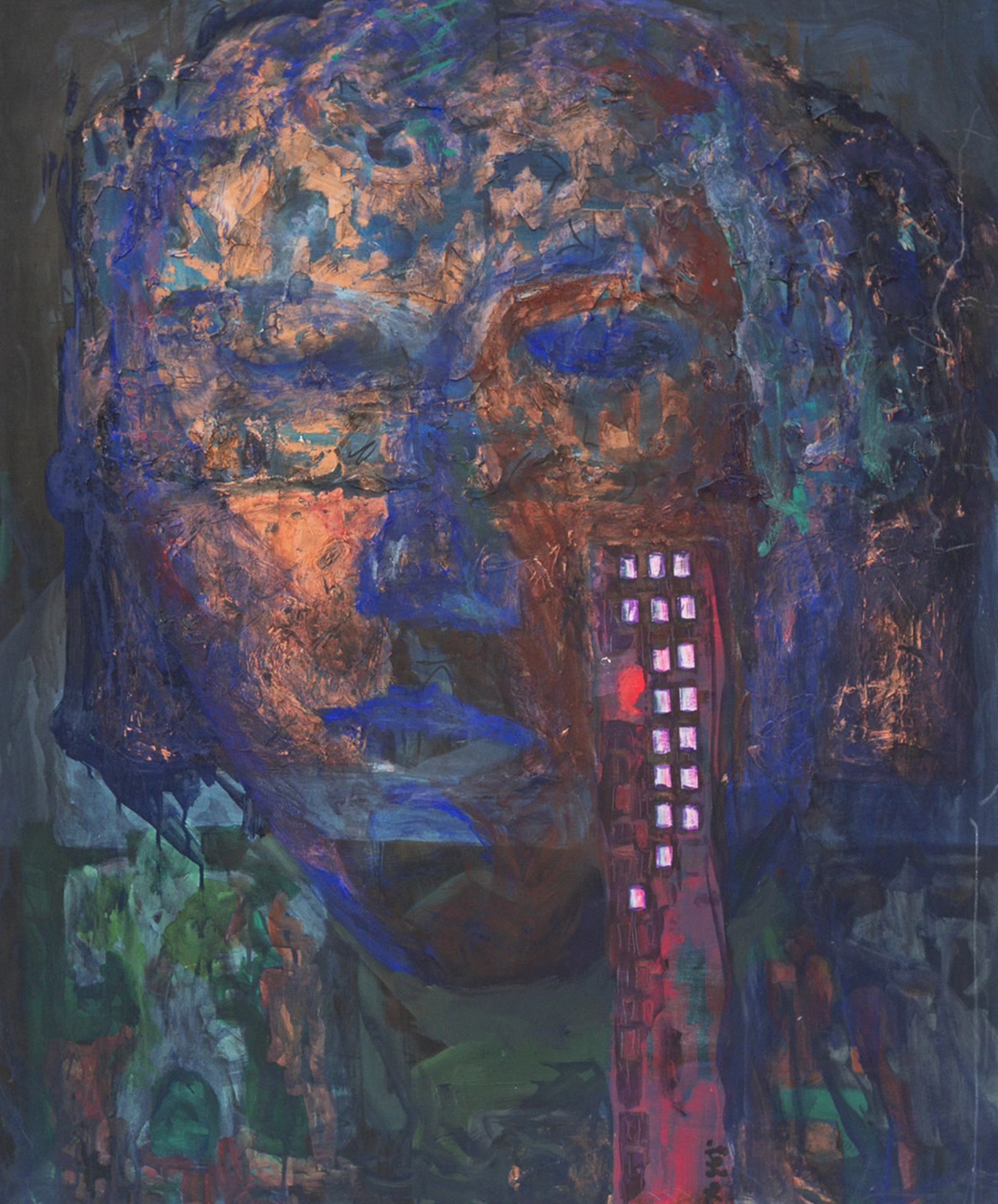

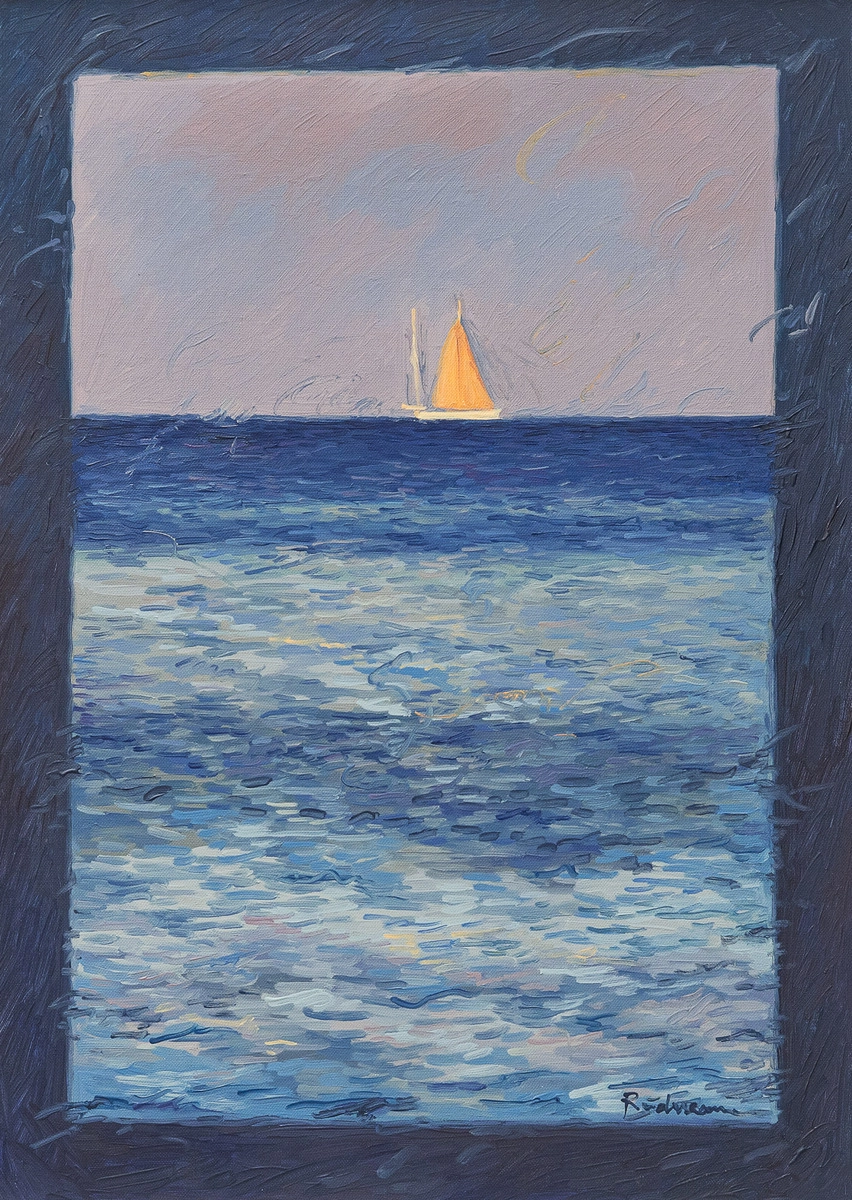

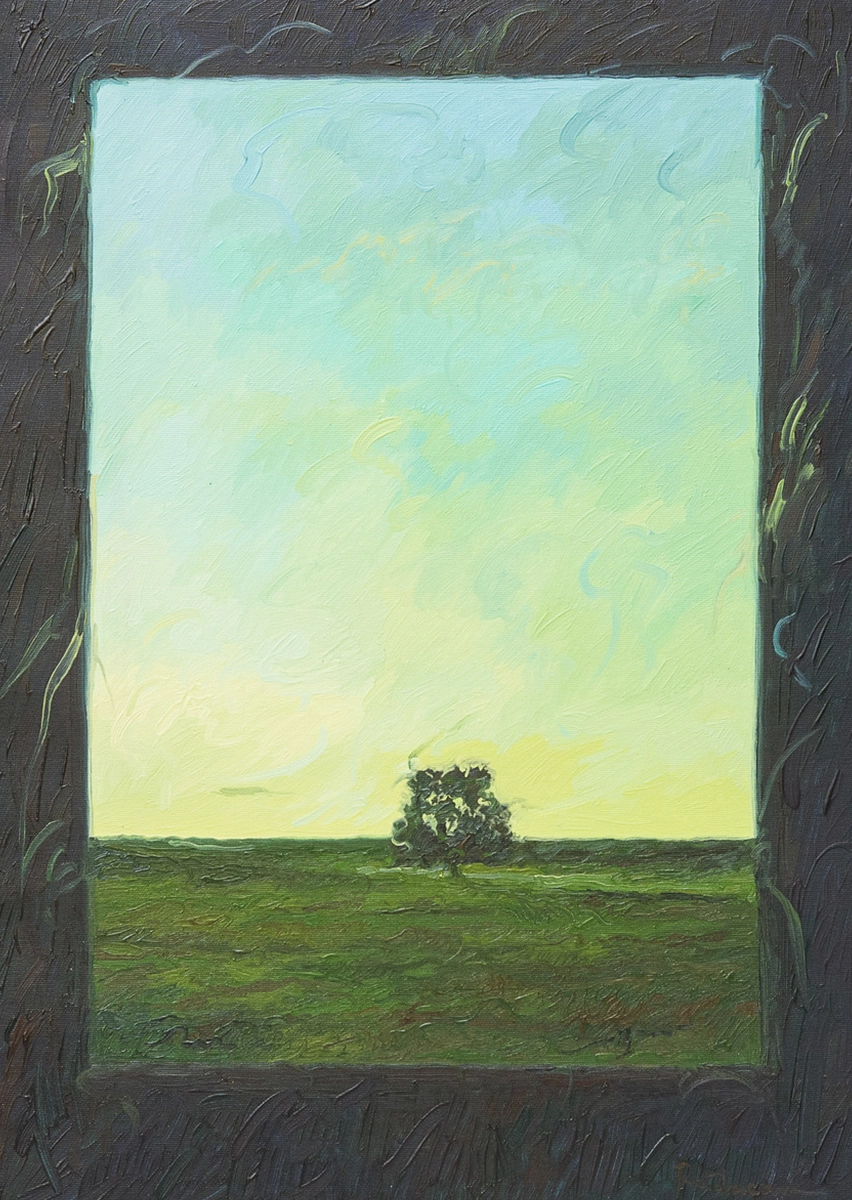

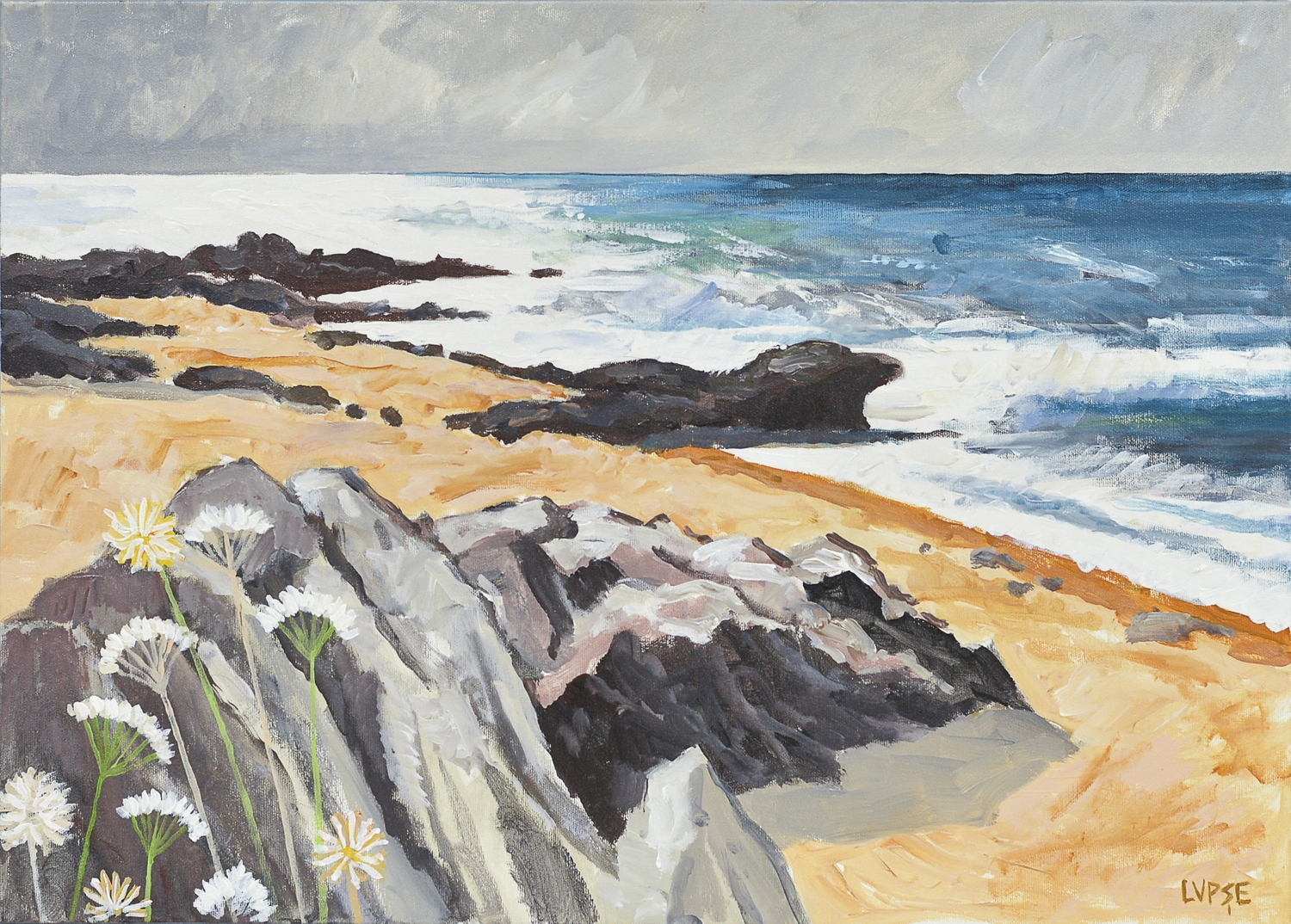

The surrounding landscape, or even the imaginary one, has been a particularly important point of reference for people, given its attributes as a framework where life could unfold or encode meanings. Landscape art generally represents the art that depicts, especially in painting, natural landscapes. With easily recognizable subjects such as forests, trees, mountains, rivers, seas, and oceans—broad vistas or even various types of gardens—the art of depicting landscapes always relies on coherent compositions. Besides paintings where the actual theme is the landscape, there are often landscape elements present in the background of famous portraits or in works where the main subject is not the scenery.

From the very beginning, paintings on this theme have rendered views of landscapes with varying degrees of precision, imagination often being used to complete, modify, or entirely invent new scenes. That is why, historically, the painted landscape has remained a subject of interest to this day, when, more often than not, the message of an image is strongly amplified by its adjacent elements.